The banking dilemma

"Of all the many ways of organizing banking, the worst is the one we have today". These words were uttered by none other than Sir Mervyn King, Governor of the Bank of England, in October 2010 at the Buttonwood Gathering in New York. It is hard not to arrive at the same conclusion.

The history of banking is filled with crises, turmoil, euphoria, depression, mass failures, high profits, wild swings, and yet, the industry seems to have learned little throughout time. The banking dilemma still haunts us: when a majority of depositors suddenly demand repayment, their money is not in the bank's vaults.

A 2008 IMF study tallied 124 banking crises since 1970. Various countries make the list. Iceland was not included back then. Neither was Europe.

In light of the current events we must ask ourselves, can modern banking be reformed? Sir Mervyn King's statement implies on the positive. There certainly are other ways of organizing banking. It is further implicit there have been better ways. But then why is our modern banking system so fragile? Why have we retrogressed instead of progressed in this vital economic activity? Why is this the only industry in need of a lender of last resort? Why does it hold a nation's economy captive? What are the necessary reforms?

Below we will attempt to briefly cover the main features of our modern banking system. Thereafter, we shall analyze the Basel III framework, since it is at present the main tool being heralded to supposedly strengthen bank's resilience to crises. Lastly, we will raise some essential questions and put forth the principles on which any banking reform shall be based upon.

Modern Banking

Several aspects of the modern banking practice are worthy of discussion. Nonetheless, we will contain our analysis to the features that most define how banks operate today, whose economic effects are not only relevant but also determinants.

Maturity Mismatch

The golden rule of banking coined by Otto Hübner in 1853 says "assets and liabilities should not have mismatched maturities". But this is not a problem confined to banks. In fact, every business must learn how to deal with its assets and liabilities maturing at different time periods. Be it a steel producer or a grocery store, businessmen must ensure its liabilities do not come due prior to its investments. A liquidity constraint may turn into a solvency problem in case assets have to be sold at fire sale prices or liabilities cannot be rolled over.

In short, banks issue short term liabilities (i.e. demand deposits, that is, debt with zero maturity) in order to finance long term investments (i.e. mortgages, business loan, etc). If depositors constantly renew their debts (by forgoing to withdraw their funds), banks face no liquidity constraint. Problems arise when sentiment change and depositors decide to take their money out of banks.

Fractional Reserve Banking

Maturity mismatch is a risky venture. The practice of fractional reserve banking is maturity mismatching on a grand scale.

If a bank takes $ 100 in cash as demand deposit and loans it out as a consumer loan to mature in two years, it has incurred in a maturity mismatch. It has issued $ 100 in short term liabilities to fund long term assets. If it fails to convert this asset in $ 100 when demanded by the depositor the bank is insolvent.

However, with fractional reserve banking, banks usually do not loan out the deposited cash. They instead create a new deposit against a new loan. Therefore, a bank's balance sheet will show $ 200 as demand deposits, $ 100 in cash and $ 100 in loans. Thus, it has 50% of cash (reserves) to meet its $ 200 liabilities. It has only a "fraction" as reserves. By realizing depositors rarely withdraw their funds, banks expand credit at great lengths, granting loans several times the original deposited cash. Banks thus create money "ex nihilo". Or as it is described in modern day economics textbooks, they multiply money. It is the "money multiplier" (more on this below).

Therefore, through fractional reserve practice, banks can issue short term liabilities while maintaining only a small fraction as short term liquid assets and the vast majority as long term investments. Throughout history, most banks were unable to survive for long under this practice, since it simply could not redeem all its liabilities in specie (gold in the past, central bank notes at present). The central bank was the logic outcome designed to remediate this shortcoming.

Central Banking

Virtually every country on earth has a central bank at the core of its financial system, whose primary functions are to issue the national currency and control interest rates (thus controlling the money supply), and act as a lender of last resort to the banking sector in times of crisis. Additionally, many central banks also take the regulatory role, whose goal is to supervise banks, implementing the myriad of regulations that attempt to ensure a stable financial system.

Fractional reserve banking is not only monitored but also encouraged by the central bank, whose main policy tool is the so called "reserve requirement", that is, how much a bank must hold as reserves against deposits. By lowering the fraction of reserves banks are mandated to hold, the central bank enables the banking system to increase the "money multiplier". Banks can now expand more credit on top of its held deposits.

We have merely covered the essential aspects of modern banking in a descriptive manner, in order for us to prepare for the analysis ahead. As we move along we will present a few critiques of the current banking arrangement.

Basel Framework

The utter failure of Basel I and especially II in anticipating the 2007 financial crisis impelled the authorities to revise and update its set of rules on banking regulation. Under the title of Basel III, a revised framework was published in haste. There are some substantial differences between Basel II and III.

Although many of the previous flaws are maintained, it is a step in the right direction. But it is only a minor one. (The following critique is far from exhaustive).

According to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, the Basel 3 proposals have two main objectives, a) To strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations with the goal of promoting a more resilient banking sector; and b) To improve the banking sector's ability to absorb shocks arising from financial and economic stress.

To achieve these objectives, the main proposal the BCBS Basel 3 has developed are: a) Capital reform (including quality and quantity of capital), complete risk coverage, leverage ratio; and b) Liquidity reform (short term and long term ratios).

Capital Ratios and Risk Weighted Assets (RWA)

In terms of capital adequacy the main differences are tougher capital requirements, both in quality and quantity. With regards to quality, there are stricter rules for capital eligibility. Common equity and retained earnings should be the predominant component of Tier 1 Capital instead of debt-like instruments.

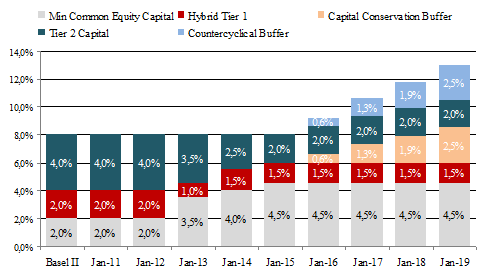

In view of preserving core Tier 1, the Committee introduced two new "buffers". A Capital Conservation Buffer should allow banks to absorb shocks in periods of stress without breaching core Tier 1. And a more discretionary Countercyclical Buffer to compensate for increased systemic risks in times of excessive credit growth.

In terms of quantity, total Tier 1 Capital is now required at 6%, up 2% from Basel II (in addition to the "buffers" which require 5% more capital, see Chart 1).

Furthermore, a new leverage ratio will make part of banking regulatory framework. Banks will be required to maintain a leverage ratio of 3 percent or more (33 times its capital). The unweighted assets include provisions, loans, off-balance sheet items with full conversion, and all derivatives. The main purpose of this ratio is to constrain leverage in the banking sector, while also helping to safeguard against model risk and measurement errors.

It is certainly congratulatory to implement tougher rules on capital adequacy ratios, but it is far from being sufficient. We must remember that on the eve of the financial crisis, many financial institutions were adequately capitalized, that is, even more than "Basel compliant". Nonetheless, they went under in less than a month. An emblematic case was a famous mortgage lender in the United Kingdom. After the UK adopted Basel II in 2007, of all the major banks the one with the highest capital ratios was Northern Rock. Within days of announcing it intended to return excess capital to shareholders, it simply ran out of money. In more than 150 years it was the first classic "bank run" the British experienced.

Defining precise capital ratios is largely an arbitrary work. Even more so is the classification of risky assets under the Basel rules. In the "standardized approach" (defined by the Basel Committee) bonds of sovereigns rated AAA to AA- require absolutely no capital, while A+ only 20%. Public sector entities also enjoy a high "safe" status under Basel.

Take Italy for instance. A bank holding Italian bonds needs only 2.1% of Tier 1 Capital (20% RWA times 10.5% of necessary Basel III Capital Ratio). That means a mere 5% haircut in Italy's debt can wipe out a bank's capital base. Let us not even remember Greece's recent haircut is 50%.

In December 2009 Greece and Italy were rated A- and A+ (Fitch), respectively. That meant a mere 1.6% of Tier 1 Capital was required (20% RWA times 8% Basel II Capital Ratio). While Portugal, Ireland and Spain required no capital whatsoever.

The whole incentive under Basel rules is to accumulate low or risk free assets leveraging its capital base to its full extent. Basel III at least caps the maximum leverage. Basel II allowed for a free ride in this respect. Securitization was a direct byproduct of capital adequacy rules. By pooling risky mortgages in a security, rating agencies gave AAA status to a pool of bad assets (how a bad mortgage when bundled together with hundreds of other bad mortgages magically turn into a high quality asset still puzzles the mind). Thus, it permitted mortgage originating banks to remove bad assets from its balance sheet, in turn encouraging investing banks from accumulating these securities while never having to bother to hold significant capital.

However, instead of using external ratings banks could also rely on an internal ratings based approach (IRB). Through this method banks were allowed to employ sophisticated financial models to determine their exposures to various risks. Despite the dramatic failure of using complex risk models which brought down Long Term Capital Management in 1998, banks were heavily determining their capital ratios through such tools (risk modeling is a crucial topic but will not be treated in depth in this newsletter).

In summary, financial modeling is highly imperfect and very judgmental. Many risks are unknowable and unquantifiable by definition. Moreover, risk models are open to great abuse and manipulation. Banks' main incentive in using models is to underestimate risk so as to enable a more leveraged (thus profitable) capital base.

Though higher capital ratios are indeed welcomed, the estimation of how much is prudent relies on arbitrary judgments. Additionally, the assessment of risky assets is wholly deficient. Both the standardized and the IRB approaches are inherently flawed.

Lastly, the Basel capital adequacy framework is largely biased toward government debt. In the original Basel Accord (1988), the debts of all OECD governments were given a risk weight of zero. It has remained virtually unaltered ever since. Should regulators then be surprised that the greatest threat to the European banking system at the moment is precisely sovereign debt?

Liquidity Ratios

Basel II focused extensively on the assets' side of bank's balance sheets, while neglecting the liquidity and liability structure of the banking system. The new Liquidity Ratios introduced by Basel III attempt to address this grave inconsistency.

In addition to the capital banks must hold against risk weighted assets, financial institutions now have two new ratios to comply with: Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and Net Stable Funding Ratio. LCR is designed to promote the short-term resilience of a bank's liquidity risk profile by ensuring that it has sufficient high-quality liquid assets to survive a significant stress scenario lasting for 30 calendar days; and the NSFR aims at promoting longer-term resilience by requiring banks to have capital or longer term high-quality funding which can survive over a one year period of less severe stress.

As laudable as this regulation is, it lies on a shaky foundation. The LCR is designed to ensure that a bank has sufficient high quality unencumbered liquid assets to enable it to survive (i.e. to allow it to meet its cash commitments arising over) a short term (30 calendar day) period of significantly severe stress. It therefore requires a bank to consider the cash outflows and cash inflows it can expect to be subject to over this period. Recognizing that it is likely to have increased commitments and less available resources, it should maintain a buffer of high quality liquid assets equal to or greater than its expected total net cash outflow. Banks will be required to meet the LCR at all times.

The LCR is supposed to serve a purpose similar to what the reserve requirements (defined by central banks) were meant to do in the past. The latter is how much cash in specie (or in central bank reserves, cash convertible at any time) banks must hold against demand deposits. The former is precisely the same, with the addition that high quality assets also qualify to satisfy the regulator. Reserve requirements in modern banking are lower than 10% in the majority of countries and even 0% in some extreme cases (Australia, Canada and New Zealand).

Two criticisms are warranted: the array of high quality assets and the method to estimate a "short term period of severe stress". I urge the reader to guess which class of assets receives undeserved high quality status once again? Yes, naturally. Sovereign debt. Not wanting to sound repetitive, I will leave it to the capital markets to decide how good these are.

Turning to our second criticism, how can banks estimate what constitute a period of severe stress? According to the BCBS, financial institutions must calculate their total expected net cash outflows under a 30 day stress scenario. With regards to outflow of cash, these "are calculated by multiplying outstanding balances of various categories or types of liabilities and off-balance sheet commitments by rates expected to run off or be drawn down" (emphasis added).

The eternal banking dilemma lies precisely on the fact that these rates are unquantifiable. Basel's LCR rests on the same principle used to substantiate the percentage of reserve requirements, the "law of large numbers". That is, in order to fulfill their customers' normal requests for liquidity, banks only need to keep on hand, in the form of a cash reserve, a fraction of the money deposited with them in cash. On LCR's case, it is cash plus other highly liquid assets to meet a 30 day severe stress.

However, for the simple fact that banking phenomena fall within the realm of human action, risks of deposit withdrawals are neither quantifiable nor insurable. Human action is subject to permanent uncertainty. Consequently, it is not an insurable (or measurable) risk. Throughout history banks have never been able to remain solvent by holding as reserves only a fraction of deposits. Basel's LCR requirement will impose a higher buffer against this uncertainty. But it will never be able to indefinitely avoid it. Let us not forget a bank run needs much less than 30 days to bring down a financial institution.

The Net Stable Funding Ration is similar to capital adequacy rules, but is somewhat stricter. It addresses the maturity mismatch intricacies by mandating banks to fund certain classes of assets with longer term liabilities (Tier 1 and 2 Capital included). Evidently, sovereign debt is among the high quality asset class. All in all, the NSFR shall clearly be an additional hindrance to balance sheet growth.

Overall, Basel III is an improvement on its failed predecessor. Capital adequacy ratios have been increased. And the Committee has finally recognized illiquidity can rapidly turn into insolvency. Alas, its arbitrary risk weights have been virtually unaltered since 1988, awarding certain classes of assets (at the very least) questionable low risk status. Perhaps the most disappointing peculiarity is the lengthy implementation time table. Key proposals are postponed to later years and full compliance is required by 2019. Something tells me banks don't have that much time.

Bank profitability (Return on Equity) will take a hit, everything else remaining equal. But it is difficult to predict how banks will react to compensate for income loss. We also have the bureaucracy burdens: reporting, disclosing, and maintaining compliance with Basel III will surely affect banks' bottom line.

In the end the Basel Framework is like a driver heading towards a cliff at 90 miles per hour, who suddenly slows down to 60, while simultaneously quitting smoking. It will surely reduce risks. It may last longer. But it won't change the end result.

True Reforms

So how can we improve the worst banking system ever? How can we ensure banks internalize the costs of maturity transformation?

The first reform we would propose has actually been put forward by two English MPs, Steven Baker and Douglas Carswell through a bill which would prohibit banks and building societies lending on the basis of demand deposits without the permission of the account holder.

Its purpose is to distinguish deposit taking for safekeeping from deposit to be loaned out by financial institutions. A simple and straightforward bill which would require banks to specify at the moment of deposit if the depositor's wish is to merely request a bank to hold on to his money or rather, he intends to authorize the bank to loan it to borrowers. This simple change would have enormous impact, once it would sort out any confusion and prevent banks from loaning depositor funds which were never intended for such fate. Lenders would be rewarded an interest rate, for meeting a borrower needs of funds, and depositors would not forcibly and unknowingly become lenders overnight.

Yes, depositors who wished a safekeeping service would probably pay to do so. In the end it depends on the contract of both depositor and bank, as long as it is a clear and enforceable contract. This initiative would greatly diminish the maturity mismatch risks banks heavily engage in at present, reducing the threats of liquidity crises.

Consequently, fractional reserve banking (FRB) would have to be reevaluated, which brings us to the second proposal. The ability to create deposits by expanding credit ex nihilo, puts the whole banking system under enormous systemic risk. Firstly, there exist the legal argument, which considers it is fraudulent for banks to create multiple claims on the same originally deposited money (an argument this author subscribe to). Secondly, by expanding credit regardless of prior voluntary savings, FRB brings about widespread malinvestments, which sooner or later must be liquidated, precisely for lack of previously saved resources. A typical boom-bust cycle.

Reducing maturity mismatch to a minimum and abolishing FRB would greatly enhance the soundness of the banking system. It would surely make it much less prone to systemic failure. Under this scenario a central bank would be irrelevant, once its main function, liquidity provision, would be virtually unnecessary.

The third and last proposal, would possibly make the first two redundant: free banking. That would entail the freedom to succeed, and more importantly, to fail. A restoration of the appropriate incentives. Abolition of the regulatory system. Above all, an entire withdrawal of the state from the financial system. It would mean the end of central banking. It would also mean ending any deposit insurance. And obviously, no bail outs either.

Internalizing the costs of the financial system is central to restore confidence in banking. Institutions should be free to reap the highly (and risky) profits of borrowing short and lending long. But they should not be allowed to socialize their losses to the remainder of society when investments turn sour. Bank owners should be held accountable for their decisions.

These set of reforms would tackle many of the issues which threatens modern banking, such as derivatives. Widely recognized as financial "weapons of mass destruction", the truth is they can only be considered as such under a scenario of implicit rescue guarantee. The truth is central bank was called for into existence not to prevent banks from taking excessive risks, but to prevent them from failing while taking excessive risks. Therein lies one of the main flaws.

It would be preferable the adoption of all three proposals. In that order. Then we can finally have free banking subject to traditional legal principles. A concept so simple, yet revolutionary in modern times. It has worked for every other industry. There is no reason to believe it would not work for banks.

Conclusion

To borrow another quote from Sir Mervyn King "this is the most serious financial crisis we have seen, at least since the Great Depression, if not ever". There is no doubt about it. And its underlying causes are intimately linked to the way of organizing banking.

Abolishing FRB and clarifying when deposits are held for safekeeping will greatly enhance the strength of banks. However, these two reforms may fail if a lender of last resort continues in operation, as banks would find innovative ways to circumvent those restrictions.

We must remember that, given the presence of an implicit bail out guarantee, regulations are simply the main obstacle on banks' way. Their incentive is to avoid it so as to achieve the highest profits possible. Derivatives, off balance sheet exposures and whatever misses the regulator supervision are valid. Dangerous financial innovations are the byproduct of banking regulations coupled with an implicit rescue guarantee. The regulator will always lag behind.

The current banking framework encourages excessive risk taking, while disregarding the consequences. Bank regulations (Basel included) induce financial institutions to operate on the edge. Complying with minimum rules, taking maximum risks, and relying on central bank rescue can never instill prudence in the banking practice. But the fear of bankruptcy can surely change behavior.

A solid financial system cannot rely solely on confidence or on the notion that most depositors will never demand repayment. To return to sound banking is to extend banks the same rules and incentives the whole economy abide by. No privileges. No subsidies. Prudent and able bankers will thrive. Those who are reckless and fraudulent will perish. And the economy will prosper.

[From VOGA Newsletter]

Comentários (0)

Deixe seu comentário