Houston, market urbanism legend

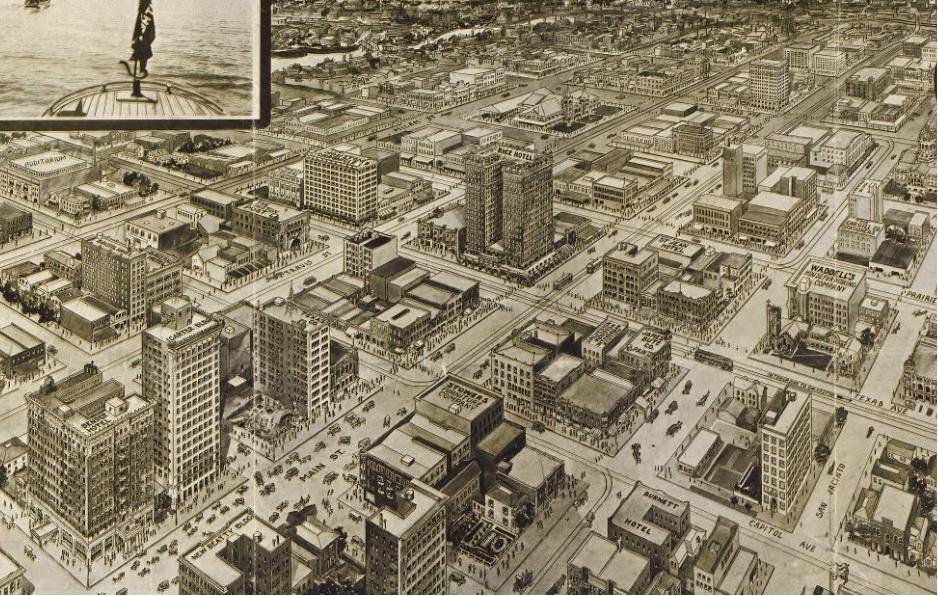

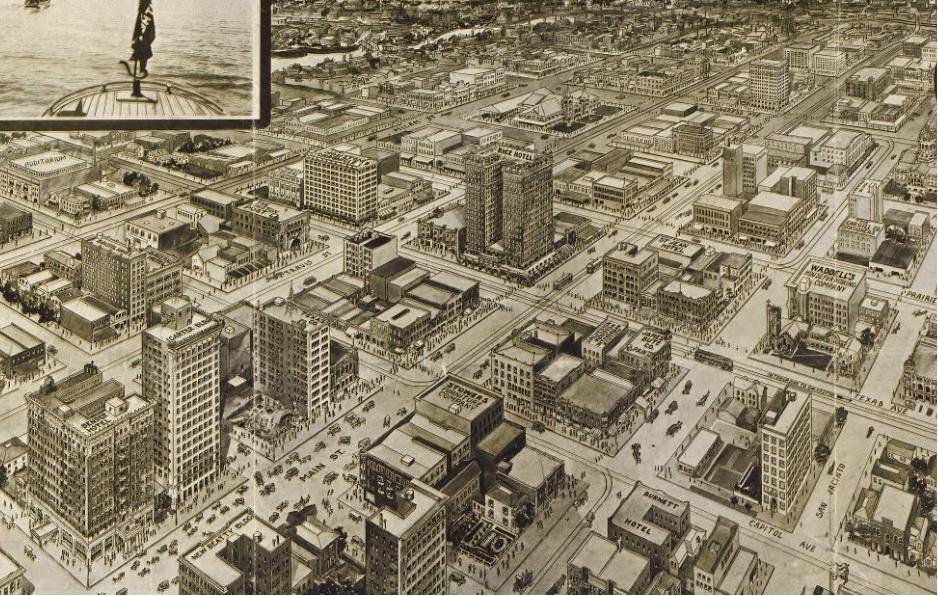

Anyone who has studied in an Architecture school, wherever it might

be, has already seen the picture on the left: a mindblowing angle of

downton Houston, the largest city in Texas. One instantly notices the

absurd amount of parking lots in one of the cities most valuable areas.

"Is this the kind of city we want?", asks the teacher. Depending on the

automobile and losing pedestrian street life, one of the most debated

issues in urbanism today, is implicit to any observer.

The largest city in a state known to be the least regulated (Texas), in the country which simbolizes freedom and deregulation to the rest of the world. For the teacher and his students the case is closed: the individualistic desire for the car and capitalist real-estate speculation using lots as parking without the needed municipal regulation is what generated this urban catastrophe. It is an undisputed fact which deserves full attention of future urban planners so this does not happen in our cities of the future.

It's definitely a motivating story, making young students enthusiastic to control their cities in a sustainable way. Unfortunately, it is false.

I'll give half a point to this story: one regulation Houston does not have is euclidian zoning, the division between residential, commercial and industrial areas*. As it is one of the most traditional ways of urban regulation, it created the urban legend that no regulation existed at all. Nevertheless, today it's harder to find urbanists who support this kind of zoning, and on both academic and blog circles much more is said about mixed used than segregated uses.

I won't give it a full point because in Houston there is covenant zoning, neighborhood associations that agree among themselves what kind of use it will have. But despite seeming voluntary and free, Houston is one of the few north-american cities where City Hall itself will act upon covenant residents who brake the rules, with the whole city paying for the legal bills. This kind of regulation makes the city just slightly less zoned, in practice, than american cities that maintain euclidian zoning rules.

But let's talk about what really matters, starting with urban form. Legislation says that block should be at least 600ft wide, roughly 200m. Urbanists recommend pedestrian oriented planning to have blocks around 300ft. Long blocks make walkability hard as pedestrians don't have exists to adjacent streets, forcing them to walk along a hallway. Jane Jacobs also commented on the importance of this feature on "Death and Life of Great American Cities":

Another feature related to urban street form is the width, or the size of the "right-of-way" in technical language. It's pretty clear that the wider the streets the worst things go for pedestrian and cyclists as cars go faster and streets are harder and more dangerous to cross. In Houston, major avenues must be at least 100ft wide (around 30m) and regular streets around 50-60ft wide (around 20m). This is the scale of the large avenues in São Paulo - hostile places for pedestrians, and keep in mind Houston sidewalks are around only 4ft wide in average.

Houston was also one of the major targets of auto-oriented planning as a way to curb transportation problems, greatly embraced by the public sector in America, North and South, in the post-war period. In the 50's the US started the Interstate Highway System of America, considered the largest public project in the history of mankind, with 75,440km of roads build and a $425 billion in taxpayer money. Cities throughout the country developed away from city centers, today commonly known as the suburbs, towards the american dream of a townhouse in a green area with cars in the garage. In Brasil we had the overpass decade, cutting up cities like São Paulo and Porto Alegre and, of course, building Brasilia in 1957, the city where sidewalks literally are nonexistent.

But this wasn't enough for Houston. Even among large american cities Houston is a top public spender in roads towards the suburbs, turning the city less and less denser and more automobile-dependent. While most american metropolis have one beltway around city centers, Houston has two and may build a third. The city only has 10% more residents than Boston with twice the number of freeways around it. Multibillion dollar projects for more road building continue to make the City Hall busy until today.

But things go even further. One of the regulations that influenced Houston even more was minimum lot sizes, which until 1998 was 5000sqft for a single-family townhouse (around 460sqm). In São Paulo, regular lots are approximately 10m x15m (150sqm), with the possibility to build multi-family or commercial buildings in this space. This anti-density pro-sprawl legislation in Houston turns mass transit virtually impossible as residents have to walk many blocks just to get to the bus stop. And as a matter of fact, every single form of mass transit is regulated by City Hall, from taxis to buses to rail.

Now guess what is the cherry on top of Houston's regulatory cake producing a downtown full of parking lots? The 1989 parking ordinance

- the good old failed attempt of the public sector trying to please its

citizens - mandating every new building to have loads of parkings

spaces. The numbers are much higher than San Francisco

which demands for 9 spaces for a high school with 18 classrooms against

171 spaces in Houston. SF demands 1 space per residence while Houston

1.25-2. In São Paulo, another great example of a traffic-oriented city

(with small lots but with a historically strong zoning code) demands 1 space for every 35-50sqm in non-residential projects, and an astonishing 3 spaces per residence when it surpasses 500sqm. Good news is that there are plans on removing this parking ordinance,

which unfortunately isn't being talked about in São Paulo, Porto Alegre

or other brazilian capitals which maintain these rules created for the

comfort of drivers.

Now guess what is the cherry on top of Houston's regulatory cake producing a downtown full of parking lots? The 1989 parking ordinance

- the good old failed attempt of the public sector trying to please its

citizens - mandating every new building to have loads of parkings

spaces. The numbers are much higher than San Francisco

which demands for 9 spaces for a high school with 18 classrooms against

171 spaces in Houston. SF demands 1 space per residence while Houston

1.25-2. In São Paulo, another great example of a traffic-oriented city

(with small lots but with a historically strong zoning code) demands 1 space for every 35-50sqm in non-residential projects, and an astonishing 3 spaces per residence when it surpasses 500sqm. Good news is that there are plans on removing this parking ordinance,

which unfortunately isn't being talked about in São Paulo, Porto Alegre

or other brazilian capitals which maintain these rules created for the

comfort of drivers.

It's also worth remembering that the city wasn't always like this. Since the beginning of the 20th century until before the automobile boom incentivized by the public sector - in a much less regulated urban environment - the city was closer to the New Urbanism ideal of today: buildings of varying heights, mixed use and high density compared to other cities at the time.

So the bottom line is that the image we see in urbanism classes is just a small part of an extremely sprawled city, where most residents have no other option of living if not isolated in the suburbs and depending on the automobile for their daily routines. After this not so brief legal and historical research it seems clear to me that the reason for this is not lack of regulation, but a pretty obvious result of the regulations enforced by the yes existing and enacting Houston Planning and Development Department.

* In practice this would naturally occur with no regulation at all, as industries don't have much incentives to buy lots in expensive dense urban areas. Downtowns themselves benefit from a spontaneous and natural existence of mixed use, as this means constant urban life.

Additional recommended reading:

"How Overregulation Creates Sprawl (Even in a City without Zoning", Michael Lewyn

"Is Houston Really Unplanned?", Stephen Smith

The largest city in a state known to be the least regulated (Texas), in the country which simbolizes freedom and deregulation to the rest of the world. For the teacher and his students the case is closed: the individualistic desire for the car and capitalist real-estate speculation using lots as parking without the needed municipal regulation is what generated this urban catastrophe. It is an undisputed fact which deserves full attention of future urban planners so this does not happen in our cities of the future.

It's definitely a motivating story, making young students enthusiastic to control their cities in a sustainable way. Unfortunately, it is false.

I'll give half a point to this story: one regulation Houston does not have is euclidian zoning, the division between residential, commercial and industrial areas*. As it is one of the most traditional ways of urban regulation, it created the urban legend that no regulation existed at all. Nevertheless, today it's harder to find urbanists who support this kind of zoning, and on both academic and blog circles much more is said about mixed used than segregated uses.

I won't give it a full point because in Houston there is covenant zoning, neighborhood associations that agree among themselves what kind of use it will have. But despite seeming voluntary and free, Houston is one of the few north-american cities where City Hall itself will act upon covenant residents who brake the rules, with the whole city paying for the legal bills. This kind of regulation makes the city just slightly less zoned, in practice, than american cities that maintain euclidian zoning rules.

But let's talk about what really matters, starting with urban form. Legislation says that block should be at least 600ft wide, roughly 200m. Urbanists recommend pedestrian oriented planning to have blocks around 300ft. Long blocks make walkability hard as pedestrians don't have exists to adjacent streets, forcing them to walk along a hallway. Jane Jacobs also commented on the importance of this feature on "Death and Life of Great American Cities":

"...frequent streets and short blocks are valuable because of the fabric of intricate cross-use that they permit among the users of a city neighbouhood."

Another feature related to urban street form is the width, or the size of the "right-of-way" in technical language. It's pretty clear that the wider the streets the worst things go for pedestrian and cyclists as cars go faster and streets are harder and more dangerous to cross. In Houston, major avenues must be at least 100ft wide (around 30m) and regular streets around 50-60ft wide (around 20m). This is the scale of the large avenues in São Paulo - hostile places for pedestrians, and keep in mind Houston sidewalks are around only 4ft wide in average.

Houston was also one of the major targets of auto-oriented planning as a way to curb transportation problems, greatly embraced by the public sector in America, North and South, in the post-war period. In the 50's the US started the Interstate Highway System of America, considered the largest public project in the history of mankind, with 75,440km of roads build and a $425 billion in taxpayer money. Cities throughout the country developed away from city centers, today commonly known as the suburbs, towards the american dream of a townhouse in a green area with cars in the garage. In Brasil we had the overpass decade, cutting up cities like São Paulo and Porto Alegre and, of course, building Brasilia in 1957, the city where sidewalks literally are nonexistent.

But this wasn't enough for Houston. Even among large american cities Houston is a top public spender in roads towards the suburbs, turning the city less and less denser and more automobile-dependent. While most american metropolis have one beltway around city centers, Houston has two and may build a third. The city only has 10% more residents than Boston with twice the number of freeways around it. Multibillion dollar projects for more road building continue to make the City Hall busy until today.

But things go even further. One of the regulations that influenced Houston even more was minimum lot sizes, which until 1998 was 5000sqft for a single-family townhouse (around 460sqm). In São Paulo, regular lots are approximately 10m x15m (150sqm), with the possibility to build multi-family or commercial buildings in this space. This anti-density pro-sprawl legislation in Houston turns mass transit virtually impossible as residents have to walk many blocks just to get to the bus stop. And as a matter of fact, every single form of mass transit is regulated by City Hall, from taxis to buses to rail.

Now guess what is the cherry on top of Houston's regulatory cake producing a downtown full of parking lots? The 1989 parking ordinance

- the good old failed attempt of the public sector trying to please its

citizens - mandating every new building to have loads of parkings

spaces. The numbers are much higher than San Francisco

which demands for 9 spaces for a high school with 18 classrooms against

171 spaces in Houston. SF demands 1 space per residence while Houston

1.25-2. In São Paulo, another great example of a traffic-oriented city

(with small lots but with a historically strong zoning code) demands 1 space for every 35-50sqm in non-residential projects, and an astonishing 3 spaces per residence when it surpasses 500sqm. Good news is that there are plans on removing this parking ordinance,

which unfortunately isn't being talked about in São Paulo, Porto Alegre

or other brazilian capitals which maintain these rules created for the

comfort of drivers.

Now guess what is the cherry on top of Houston's regulatory cake producing a downtown full of parking lots? The 1989 parking ordinance

- the good old failed attempt of the public sector trying to please its

citizens - mandating every new building to have loads of parkings

spaces. The numbers are much higher than San Francisco

which demands for 9 spaces for a high school with 18 classrooms against

171 spaces in Houston. SF demands 1 space per residence while Houston

1.25-2. In São Paulo, another great example of a traffic-oriented city

(with small lots but with a historically strong zoning code) demands 1 space for every 35-50sqm in non-residential projects, and an astonishing 3 spaces per residence when it surpasses 500sqm. Good news is that there are plans on removing this parking ordinance,

which unfortunately isn't being talked about in São Paulo, Porto Alegre

or other brazilian capitals which maintain these rules created for the

comfort of drivers. It's also worth remembering that the city wasn't always like this. Since the beginning of the 20th century until before the automobile boom incentivized by the public sector - in a much less regulated urban environment - the city was closer to the New Urbanism ideal of today: buildings of varying heights, mixed use and high density compared to other cities at the time.

So the bottom line is that the image we see in urbanism classes is just a small part of an extremely sprawled city, where most residents have no other option of living if not isolated in the suburbs and depending on the automobile for their daily routines. After this not so brief legal and historical research it seems clear to me that the reason for this is not lack of regulation, but a pretty obvious result of the regulations enforced by the yes existing and enacting Houston Planning and Development Department.

* In practice this would naturally occur with no regulation at all, as industries don't have much incentives to buy lots in expensive dense urban areas. Downtowns themselves benefit from a spontaneous and natural existence of mixed use, as this means constant urban life.

Additional recommended reading:

"How Overregulation Creates Sprawl (Even in a City without Zoning", Michael Lewyn

"Is Houston Really Unplanned?", Stephen Smith

Comentários (0)

Deixe seu comentário